AIDS Cure?

How do you cure a man of both leukemia and AIDS with just one procedure? No, it’s not a trick question: an American leukemia patient living in Berlin received a bone marrow transplant that also resolved his AIDS.

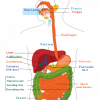

In a bone marrow transplant, a patient’s own marrow is destroyed and replaced with tissue from a donor. The donor marrow contains healthy hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs, adult stem cells in the blood) which repopulate the patient’s body with healthy red and white blood cells for oxygen transport and immune defense. Just as with other varieties of organ donation, tissue-type matches are critical. In the case of the AIDS patient, another screen was also applied: his doctors searched for donors whose cells were also resistant to HIV infection.

In order to infect a white blood cell, HIV must latch onto 2 receptors on the cell’s surface: the cd4 receptor and the CCR5 receptor. Some people have no CCR5 receptors due to mutations in the genes encoding the protein—those people are highly resistant to HIV infection. The AIDS patient received bone marrow from a donor whose HSCs (and subsequent white blood cells) could not produce the CCR5 receptor: his new cells cannot be infected by the HIV that decimated his old cells. The AIDS patient was, rather ironically, cured by receiving “defective” cells. The absence of a CCR5 receptor does not appear to affect normal physiology.

Bone marrow transplants are, unfortunately, not a feasible treatment option for the 33.4 million people infected with HIV worldwide. Patients receiving the transplant are at major risk for infection as they wait for their immune systems to regenerate: between 10 and 30% of patients die from the procedure. In addition, there are very few HIV resistant donors relative to the number of infected individuals. On average, 1 of every 1,000 Europeans carries 2 copies of the defective gene while the mutation (a 32 base pair deletion) is very rare in people of Asian and African descent.

The tidings are not all together grim, however. This case shows that HIV can be treated by inhibiting CCR5 expression. If a patient’s HSC could be removed, rehabilitated via gene therapy, and returned to the patient, future AIDS treatment might not require life-long drug courses or dangerous transplants.

| Print article | This entry was posted by Tedi Setton on February 5, 2010 at 5:49 pm, and is filed under DNA Interactive. Follow any responses to this post through RSS 2.0. You can skip to the end and leave a response. Pinging is currently not allowed. |