Medicine or Poison? It’s in Your Genes, duh…

As the ongoing deciphering of the human genome provides us with more and more insights about our predisposition for diseases and genetic disorders, (see Your Genes Your Health for examples) I am equally, if not more astounded by what it tells us about our ability to utilize medicines to counteract diseases.

As the ongoing deciphering of the human genome provides us with more and more insights about our predisposition for diseases and genetic disorders, (see Your Genes Your Health for examples) I am equally, if not more astounded by what it tells us about our ability to utilize medicines to counteract diseases.

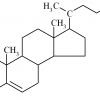

Just recently, a group of researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine have identified a variant of a gene that is believed to play a major role in determining why people do not respond to a popular anti-clotting medication. This gene variant, carried by as many as a third of the general population can put patients at increased risk for subsequent heart attacks, strokes and other serious cardiovascular problems. The interesting thing is, that this increased risk is not due to patients genetic predisposition for these disorders, but because it renders their medication ineffective.

Medicines that we introduce into our bodies often require one or several important mechanisms to unfold their intended effects: they may have to be actively transported into our cells, biochemically altered and thereby activated, or they may require deactivation and/or removal in order to not do more harm then good. Any of these processes may involve proteins on one level or another and, therefore, depend on genes. Thus, as we have maps that indicate the loci associated with genetic disorders (visit Tour > genome spots in DNA Interactive), we will soon have maps that tell us where to look if we wish to know our predisposition to the medications we use to cure ailments: whether they will do us any good, are totally useless or, in a worst case scenario, can even harm us.

| Print article | This entry was posted by Uwe Hilgert on September 24, 2009 at 4:48 pm, and is filed under Your Genes, Your Health. Follow any responses to this post through RSS 2.0. You can skip to the end and leave a response. Pinging is currently not allowed. |